Notes | Convex Optimization | Chapter3 Convex functions

3.1 Basic properties and examples

3.1.1 Definition

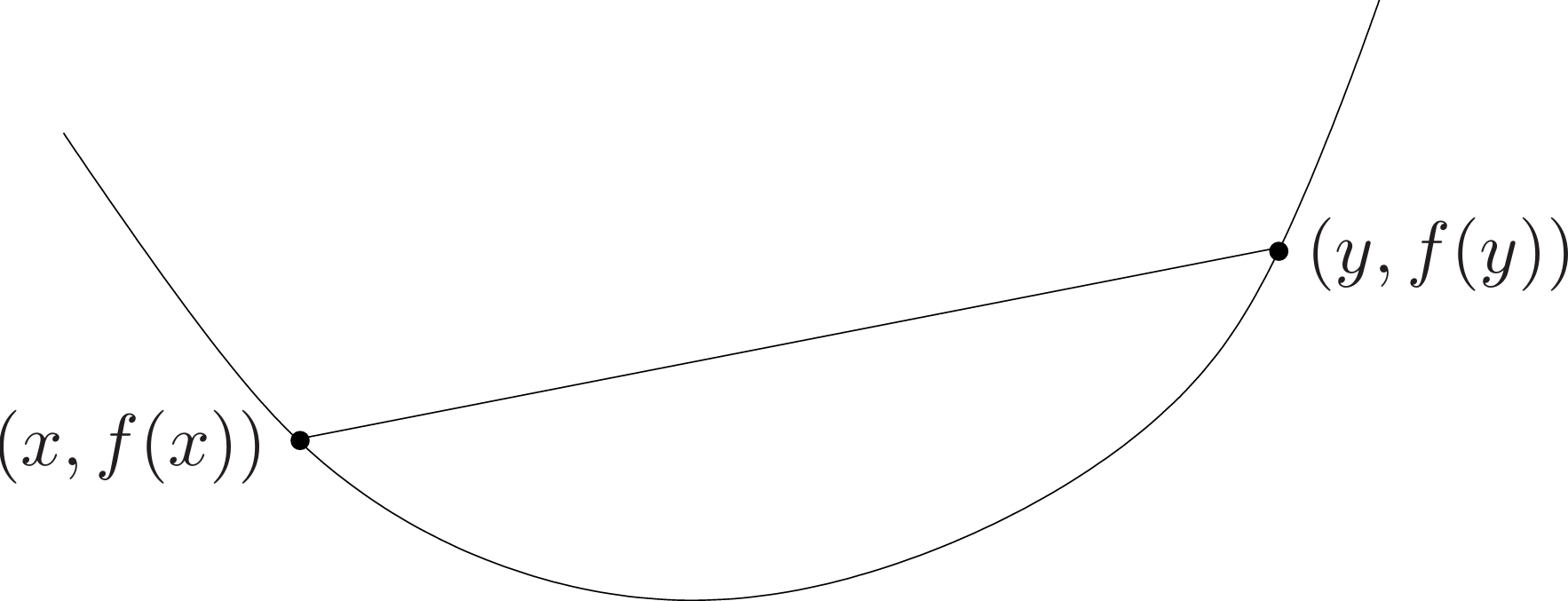

A function $f:\mathbf{R}^{n}\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is convex if $\mathbf{dom }f$ is a convex set and if for all $x,y\in\mathbf{dom }f$, and $\theta$ with $0\leq\theta\leq1$, we have

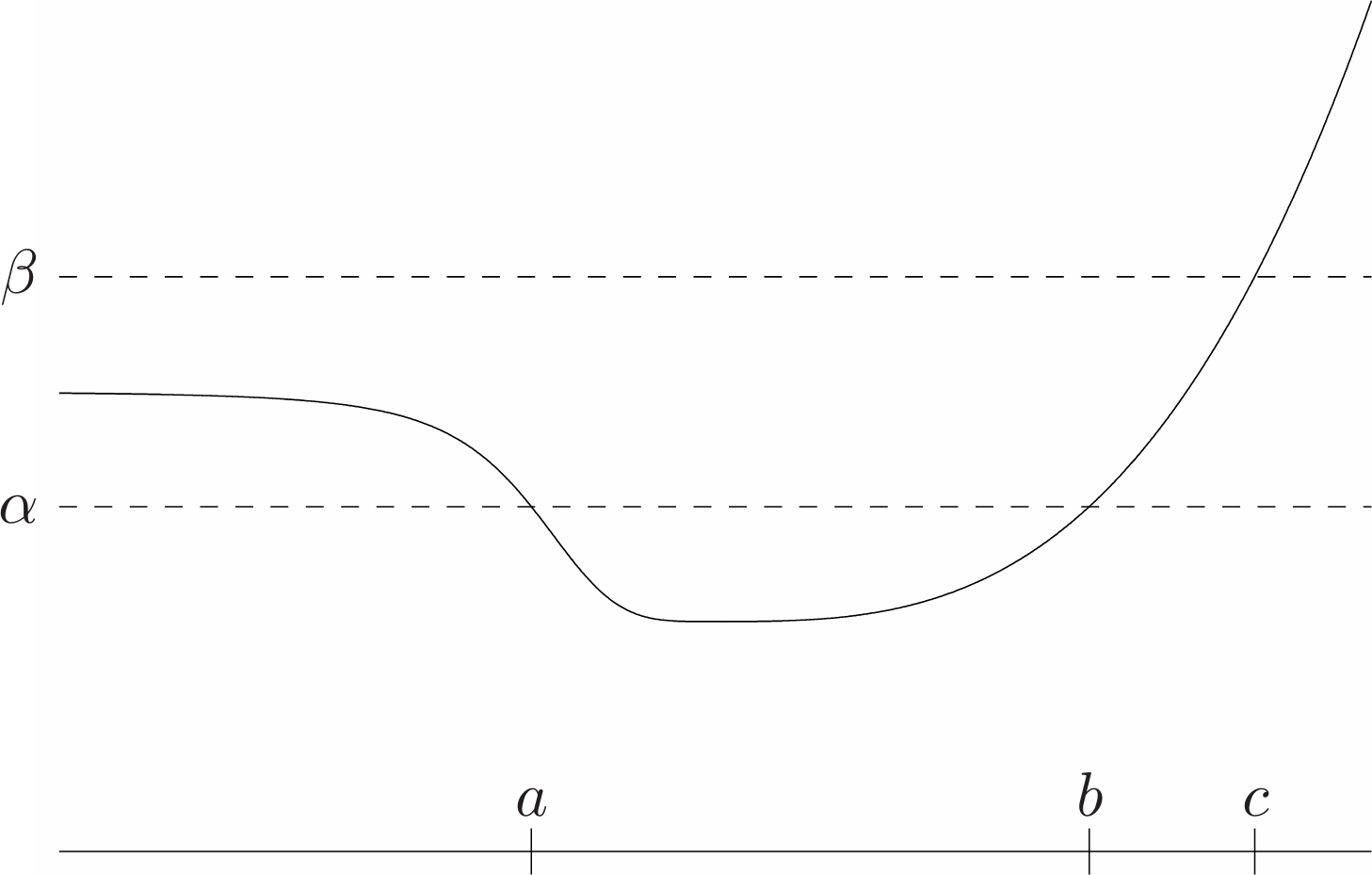

\[f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\leq\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y) \tag{3.1}\]Geometrically, this inequality means that the line segment between $(x,f(x))$ and $(y, f(y))$, which is the chord from $x$ to $y$, lies above the graph of $f$ (Fig. 1.). A function $f$ is strictly convex if strict inequality holds in (3.1) whenever $x=y$ and $0<\theta<1$.

We say $f$ is concave if $-f$ is convex, and strictly concave if $-f$ is strictly convex.

3.1.2 Extended-value extensions

If $f$ is convex we define its extended-value extension $\tilde{f}:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}\cup\{\infin\}$ by

\[\tilde{f}(x)=\left\\{\begin{aligned}&f(x)\quad&x\in\mathbf{dom } f\\\\&\infin\quad&x\notin\mathbf{dom }f\end{aligned}\right.\]| The extension $\tilde{f}$ is defined on all $\mathbf{R}^n$, and takes values in $\mathbf{R}\cup\{\infin\}$. We can recover the domain of the original function $f$ from the extension $\tilde{f}$ as $\mathbf{dom }f=\{x | \tilde{f}(x)<\infin\}$. In terms of the extension $\tilde{f}$, we can express the inequality (3.1) as: for $0<\theta<1$, |

3.1.3 First-order conditions

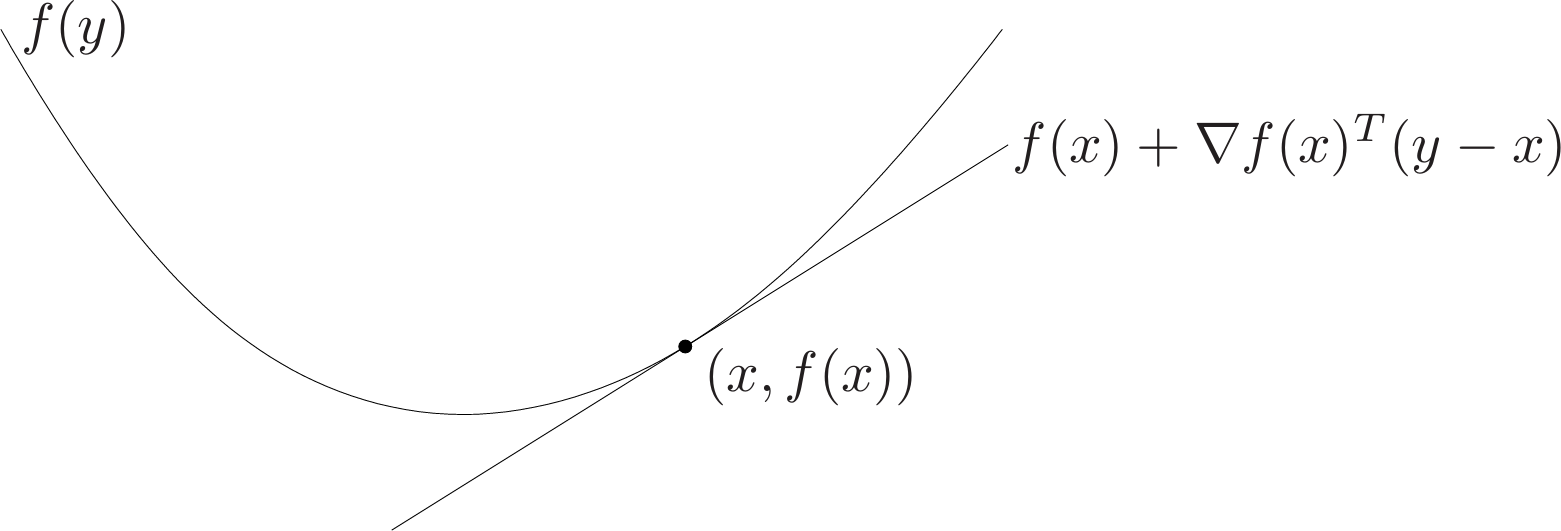

Suppose $f$ is differentiable (i.e., its gradient $\nabla f$ exists at each point in $\mathbf{dom }f$, which is open). Then $f$ is convex if and only if $\mathbf{dom }f$ is convex and

\[f(y)\geq f(x)+\nabla f(x)^T(y-x) \tag{3.2}\]holds for all $x,y\in\mathbf{dom}f$.

The inequality (3.2) states that for a convex function, the first-order Taylor approximation is in fact a global underestimator of the function. Conversely, if the first-order Taylor approximation of a function is always a global underestimator of the function, then the function is convex.

Proof of first-order convexity condition:

To prove (3.2), we first consider the case $n=1$: We show that a differentiable function $f:\mathbf{R}\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is convex if and only if

\[f(y)\geq f(x)+f'(x)(y-x) \tag{3.3}\]for all $x$ and $y$ in $\mathbf{dom}f$.

Assume first that $f$ is convex and $x,y\in\mathbf{dom}f$. Since $\mathbf{dom}f$ is convex (i.e., an interval), we conclude that for all $0<t\leq1,x+t(y-x)\in\mathbf{dom}f$, and by convexity of $f$,

\[f(x+t(y-x))\leq(1-t)f(x)+tf(y)\]If we devide both sides by $t$, we obtain

\[f(y)\geq f(x)+\frac{f(x+t(y-x))-f(x)}{t}\]and taking the limit as $t\rightarrow0$ yields (3.3).

To show sufficiency, assume the function satisfies (3.3) for all $x$ and $y$ in $\mathbf{dom}f$ (which is an interval). Choose any $x\neq y$, and $0\leq\theta\leq1$, and let $z=\theta x+(1−\theta)y$. Applying (3.3) twice yields

\[f(x)\geq f(z)+f'(z)(x-z),\quad f(y)\geq f(z)+f'(z)(y-z)\]Multiplying the first inequality by $\theta$, the second by $1-\theta$, and adding them yields

\[\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y)\geq f(z)\]which proves that $f$ is convex.

Now we can prove the general case, with $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$. Let $x,y\in\mathbf{R}^n$ and consider $f$ restricted to the line passing through them, i.e., the function defined by $g(t)=f(ty+(1-t)x)$, so $g’(t)=\nabla f(ty+(1-t)x)^T(y-x)$.

First assume $f$ is convex, which implies $g$ is convex, so by the argument above we have $g(1)\geq g(0)+g’(0)$, which means

\[f(y)\geq f(x)+\nabla f(x)^T(y-x)\]Now assume that this inequality holds for any $x$ and $y$, so if $ty+(1-t)x\in\mathbf{dom}f$ and $\tilde{t}y+(1-\tilde{t})x\in\mathbf{dom}f$, we have

\[f(ty+(1-t)x)\geq f(\tilde{t}y+(1-\tilde{t})x)+\nabla f(\tilde{t}y+(1-\tilde{t})x)^T(y-x)(t-\tilde{t})\]i.e., $g(t)\geq g(\tilde{t})+g’(\tilde{t})(t-\tilde{t})$. We have seen that this implies that $g$ is convex.

3.1.4 Second-order conditions

We now assume that $f$ is twice differentiable, that is, its Hessian or second derivative $\nabla^2f$ exists at each point in $\mathbf{dom}f$. which is open. Then $f$ is convex if and only if $\mathbf{dom}f$ is convex and its Hessian is positive semidefinite: for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$,

\[\nabla^2f(x)\succeq 0\]The condition $\nabla^2f(x)\succeq 0$ can be interpreted geometrically as the requirement that the graph of the function have positive (upward) curvature at $x$.

The function $f:\mathbf{R}\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ given by $f(x)=x^4$ is strictly convex but has zero second derivative at $x=0$.

3.1.5 Examples

In this section we give a few more examples of convex and concave functions. We start with some functions on $\mathbf{R}$, with variable $x$, then give a few interesting examples of functions on $\mathbf{R}^n$.

- Exponential. $e^{ax}$ is convex on $\mathbf{R}$, for any $a\in\mathbf{R}$.

- Powers. $x^{a}$ is convex on $\mathbf{R}_{++}$ when $a\geq 1$ or $a\leq 0$, and concave for $0\leq a\leq 1$.

- Powers of absolute value. $\lvert x\rvert ^p$, for $p\geq 1$, is convex on $\mathbf{R}$.

- Logarithm. $\log{x}$ is concave on $\mathbf{R}_{++}$.

- Negative entropy. $x\log{x}$ (either on $\mathbf{R} _{++}$, or on $\mathbf{R} _{+}$, defined as 0 for $x=0$) is convex.

- Norms. Every norm on $\mathbf{R}^n$ is convex.

- Max function. $f(x)=\max\{x_1,\dots,x_n\}$ is convex on $\mathbf{R}^n$.

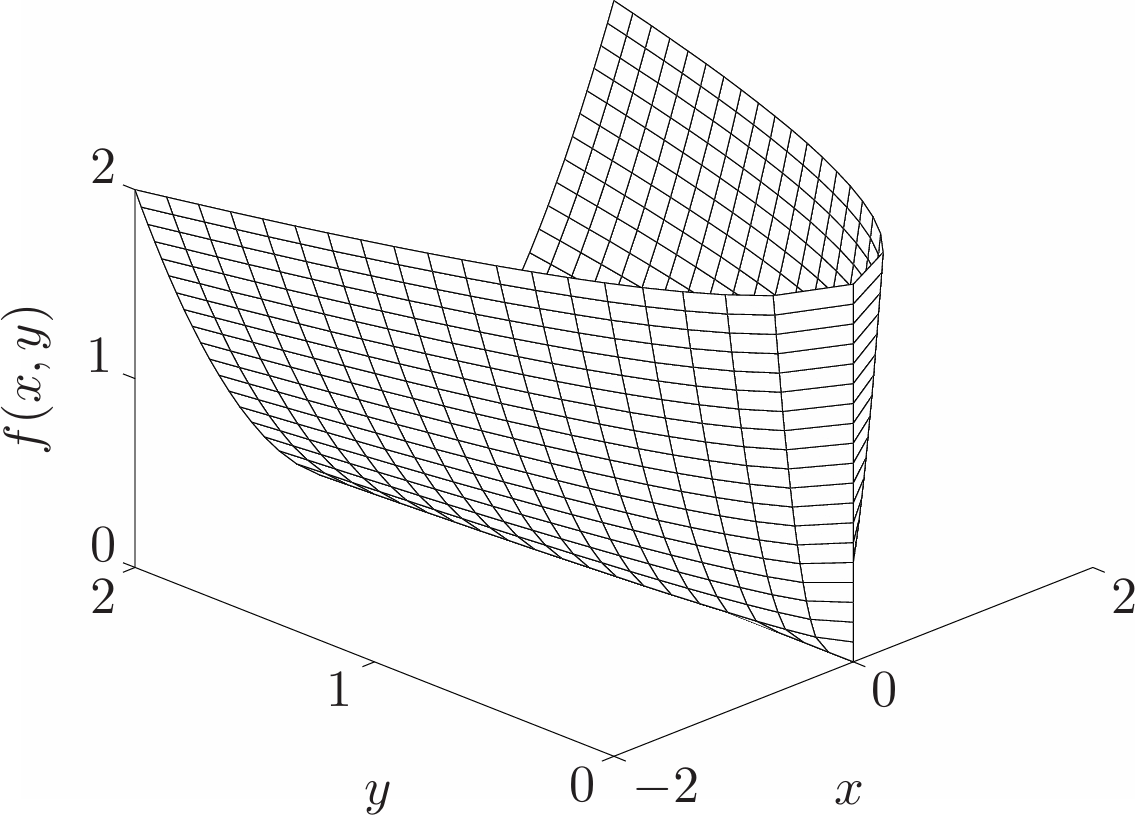

- Quadratic-over-linear function. The function $f(x,y)=x^2/y$, with \(\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{R}\times\mathbf{R}_{++}=\\{(x,y)\in\mathbf{R}^2|y>0\\}\) is convex.

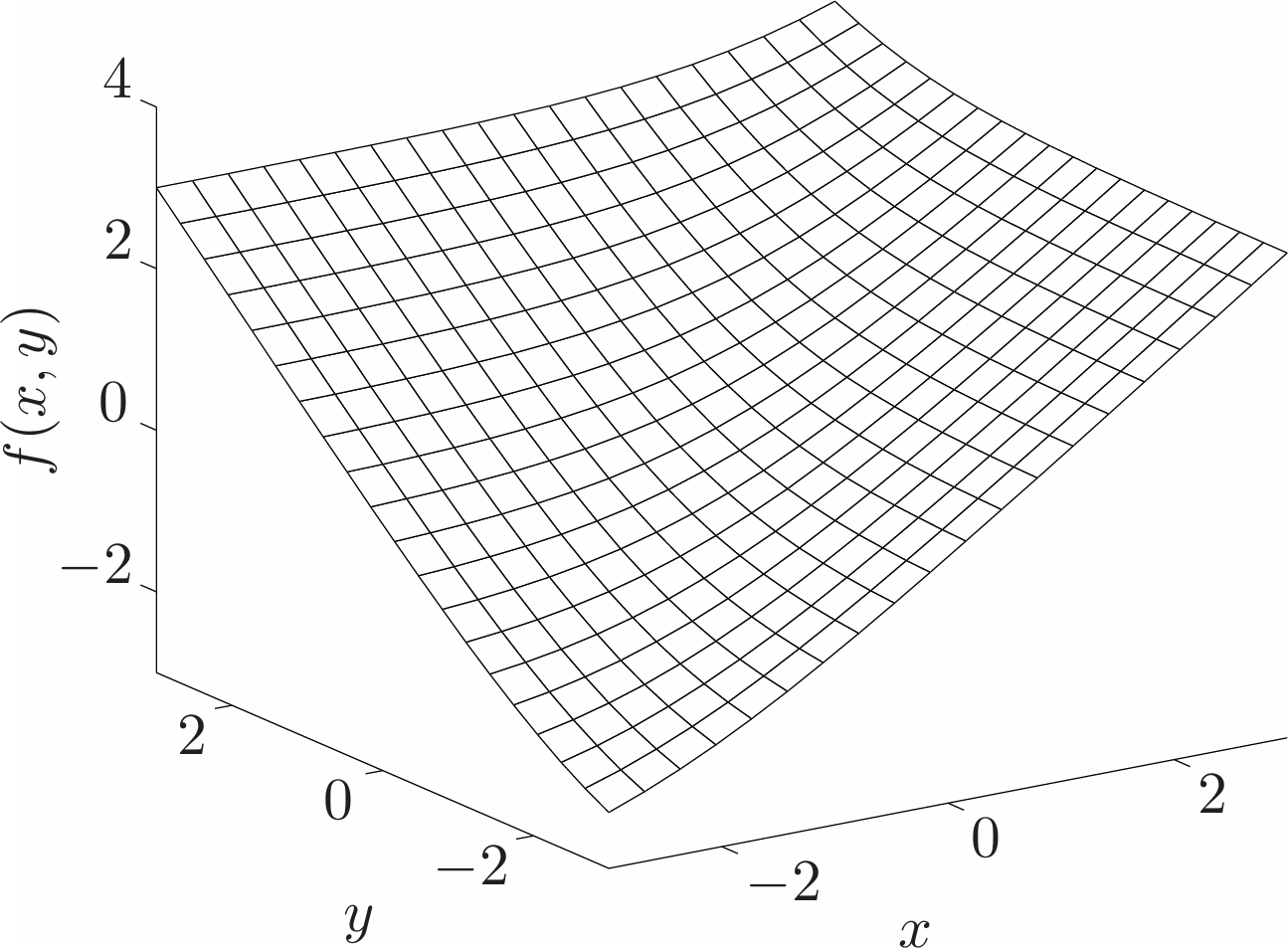

- Log-sum-exp. The function $f(x)=\log(e^{x_1}+\cdots+e^{x_n})$ is convex on $\mathbf{R}^n$. This function can be interpreted as a differentiable (in fact, analytic) approximation of the max function, since \(\max\\{x_1,\dots,x_n\\}\leq f(x)\leq\max\\{x_1,\dots,x_n\\}+\log{n}\) for all $x$.

- Geometric mean. The geometric mean $f(x)=(\Pi_{i=1}^nx_i)^{1/n}$ is concave on $\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{R}_{++}^n$.

- Log-determinant. The function $f(X)=\log\det{X}$ is concave on $\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{S}_{++}^n$.

3.1.6 Sublevel sets

The $\alpha$-sublevel set of a function $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is defined as

\[C_\alpha=\\{x\in\mathbf{dom}f|f(x)\leq\alpha\\}\]Sublevel sets of a convex function are convex, for any value of $\alpha$.

The converse is not true: a function can have all its sublevel sets convex, but not to be a convex function. For example, $f(x)=-e^x$ is not convex on $\mathbf{R}$ (indeed, it is strictly concave) but all its sublevel sets are convex.

| If $f$ is concave, then its $\alpha$-superlevel set, given by $\{x\in\mathbf{dom}f | f(x)\geq\alpha\}$, is a convex set. |

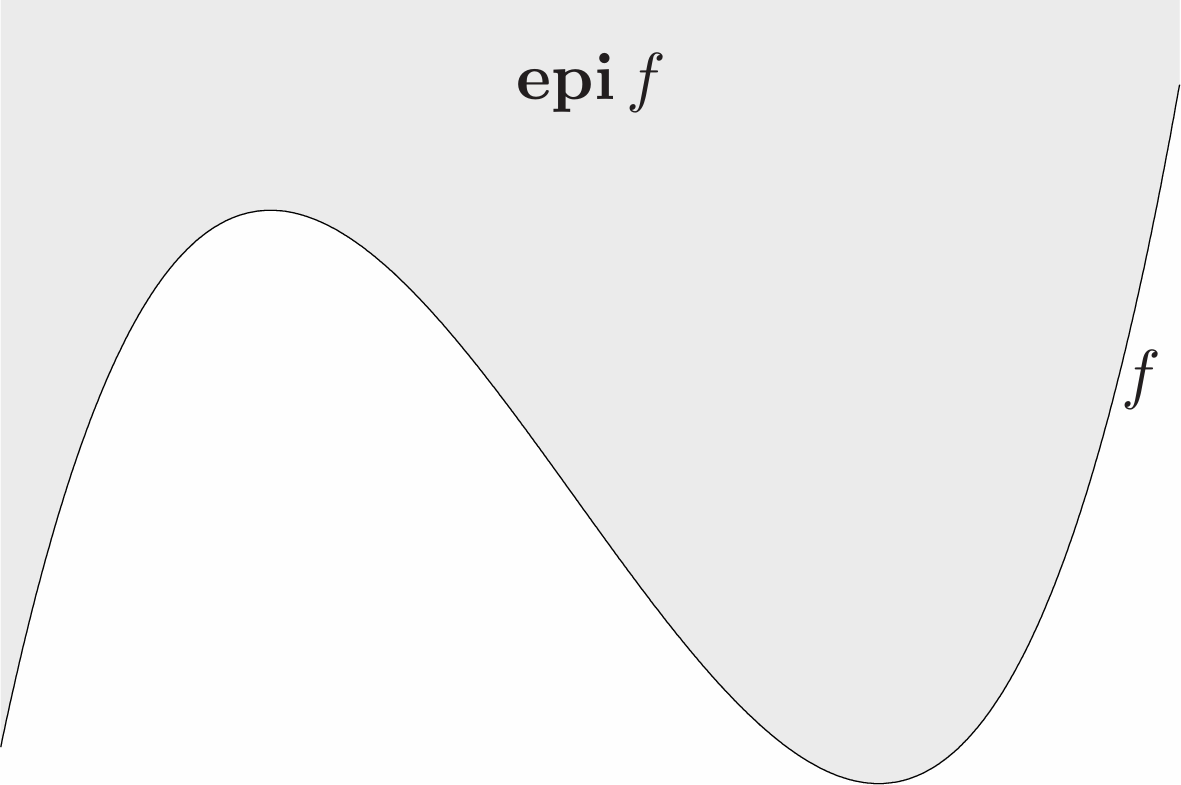

3.1.7 Epigraph

The graph of a function $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is defined as

\[\\{(x,f(x))|x\in\mathbf{dom}f\\}\]which is a subset of $\mathbf{R}^{n+1}$. The epigraph of a function $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is defined as

\[\mathbf{epi}f=\\{(x,t)|x\in\mathbf{dom}f,f(x)\leq t\\}\]which is a subset of $\mathbf{R}^{n+1}$. (‘Epi’ means ‘above’ so epigraph means ‘above the graph’.) The definition is illustrated in Fig. 5.

The link between convex sets and convex functions is via the epigraph: A function is convex if and only if its epigraph is a convex set. A function is concave if and only if its hypograph, defined as

\[\mathbf{hypo}f=\\{(x,t)|t\leq f(x)\\}\]is a convex set.

3.1.8 Jensen’s inequality and extensions

The basic inequality (3.1), i.e.,

\[f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\leq\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y)\]is sometimes called Jensen’s inequality. It is easily extended to convex combinations of more that two points: If $f$ is convex, $x_1,\dots,x_k\in\mathbf{dom}f$, and $\theta_1,\dots,\theta_k\geq0$ with $\theta_1+\cdots+\theta_k=1$, then

\[f(\theta_1x_1+\cdots+\theta_kx_k)\leq\theta_1f(x_1)+\cdots+\theta_kf(x_k)\]As in the case of convex sets, the inequality extends to infinite sums, integrals, and expected values. For example, if $p(x)\geq 0$ on $S\subseteq\mathbf{dom}f, \int_Sp(x)dx=1$, then

\[f\left(\int_Sp(x)xdx\right)\leq\int_Sf(x)p(x)dx\]provided the integrals exist. In the most general case we can take any probability measure with support in $\mathbf{dom}f$. If $x$ is a random variable such that $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$ with probability one, and $f$ is convex, then we have

\[f(\mathbf{E}x)\leq\mathbf{E}f(x) \tag{3.4}\]provided the expectations exist.

If $f$ is not convex, there is a random variable $x$, with $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$ with probability one, such that $f(\mathbf{E}x)>\mathbf{E}f(x)$.

3.2 Operations that preserve convexity

3.2.1 Nonnegative weighted sums

Combining nonnegative scaling and addition, we see that the set of convex functinos is itself a convex cone: a nonnegative weighted sum of convex functions,

\[f=w_1f_1+\cdots+w_mf_m\]is convex. Similarly, a nonnegative weighted sum of concave functions is concave.

These properties extend to infinite sums and integrals. For example if $f(x,y)$ is convex in $x$ for each $y\in\mathcal{A}$, and $w(y)\geq 0$ for each $y\in A$, then the function $g$ defined as

\[g(x)=\int_\mathcal{A}w(y)f(x,y)dy\]is convex in $x$ (provided the integral exists).

3.2.2 Composition with an affine mapping

Suppose $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R},A\in\mathbf{R}^{n\times m}$, and $b\in\mathbf{R}^n$. Define $g:\mathbf{R}^m\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ by

\[g(x)=f(Ax+b)\]| with $\mathbf{dom}g=\{x | Ax+b\in\mathbf{dom}f\}$. Then if $f$ is convex, so is $g$; if $f$ is concave, so is $g$. |

3.2.3 Pointwise maximum and supremum

If $f_1$ and $f_2$ are convex functions then their pointwise maximum $f$, defined by

\[f(x)=\max\\{f_1(x),f_2(x)\\}\]with $\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{dom}f_1\cap\mathbf{dom}f_2$, is also convex.

The pointwise maximum property extends to the pointwise supremum over an infinite set of convex functions. If for each $y\in\mathcal{A}$, $f(x,y)$ is convex in $x$, then the function $g$, defined as

\[g(x)=\sup_{y\in\mathcal{A}}f(x,y) \tag{3.5}\]is convex in $x$. Here the domain of $g$ is

\[\mathbf{dom}g=\\{x|(x,y)\in\mathbf{dom}f\text{ for all }y\in\mathcal{A},\sup_{y\in\mathcal{A}}f(x,y)<\infin\\}\]Simiarly, the pointwise infimum of a set of concave functions is a concave function.

Representation as pointwise supremum of affine functions:

Almost every convex function can be expressed as the pointwise supremum of a family of affine functions. For example, if $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is convex, with $\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{R}^n$, then we have

\[f(x)=\sup\\{g(x)|g\text{ affine},g(z)\leq f(z)\text{ for all }z\\}\]In other words, $f$ is the pointwise supremum of the set of all affine global underestimators of it.

3.2.4 Composition

In this section we examine conditions on $h:\mathbf{R}^k\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ and $g:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}^k$ that guarantee convexity or concavity of their composition $f=h\circ g:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$, defined by

\[f(x)=h(g(x)),\quad\mathbf{dom}f=\\{x\in\mathbf{dom}g|g(x)\in\mathbf{dom}h\\}\]Scalar composition:

- $f$ is convex if $h$ is convex, $\tilde{h}$ is nondecreasing, and $g$ is convex,

- $f$ is convex if $h$ is convex, $\tilde{h}$ is nonincreasing, and $g$ is concave,

- $f$ is concave if $h$ is concave, $\tilde{h}$ is nondecreasing, and $g$ is concave,

- $f$ is concave if $h$ is concave, $\tilde{h}$ is nonincreasing, and $g$ is convex.

Here $\tilde{h}$ denotes the extended-value extension of the function $h$, which assigns the value $\infin(-\infin)$ to points not in $\mathbf{dom}h$ for $h$ convex (concave).

Vector composition:

We now turn to the more complicated case when $k\geq1$. Suppose

\[f(x)=h(g(x))=h(g_1(x),\dots,g_k(x))\]with $h:\mathbf{R}^k\rightarrow\mathbf{R},g_i:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$. Again without loss of generality we can assume $n=1$. As in the case $k=1$, we start by assuming the functions are twice differentiable, with $\mathbf{dom}g=\mathbf{R}$ and $\mathbf{dom}h=\mathbf{R}^k$, in order to discover the composition rules. We have

\[f^{\prime\prime}(x)=g^\prime(x)^T\nabla^2h(g(x))g^\prime(x)+\nabla h(g(x))^Tg^{\prime\prime}(x) \tag{3.6}\]Again the issue is to determine conditions under which $f^{\prime\prime}(x)\geq 0$ for all $x$ (or $f^{\prime\prime}(x)\leq 0$ for all $x$ for concavity). From (3.6) we can derive many rules, for example:

- $f$ is convex if $h$ is convex, $h$ is nondecreasing in each argument, and $g_i$ are convex,

- $f$ is convex if $h$ is convex, $h$ is nonincreasing in each argument, and $g_i$ are concave,

- $f$ is concave if $h$ is concave, $h$ is nondecreasing in each argument, and $g_i$ are concave.

3.2.5 Minimization

We have seen that the maximum or supremum of an arbitrary family of convex functions is convex. It turns out that some special forms of minimization also yield convex functions. If $f$ is convex in $(x,y)$, and $C$ is a convex nonempty set, then the function

\[g(x)=\inf_{y\in C}f(x,y)\]is convex in $x$, provided $g(x)>-\infin$ for all $x$.

3.2.6 Perspective of a function

If $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$, then the perspective of $f$ is the function $g:\mathbf{R}^{n+1}\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ defined by

\[g(x,t)=tf(x/t)\]with domain

\[\mathbf{dom}g=\\{(x,t)|x/t\in\mathbf{dom}f,t>0\\}\]The perspective operation preserves convexity: If $f$ is a convex function, then so is its perspective function $g$. Similarly, if $f$ is concave, then so is $g$.

3.3 The conjugate function

3.3.1 Definition and examples

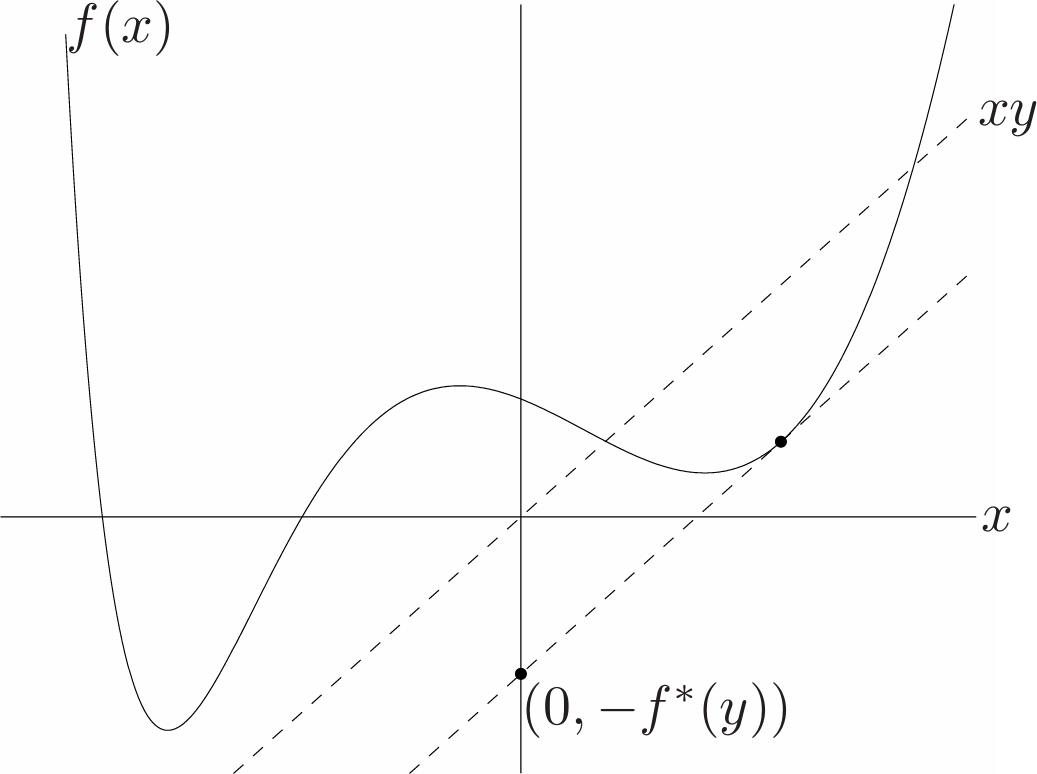

Let $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$. The function $f^{*}:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$, defined as

\[f^{*}(y)=\sup_{x\in\mathbf{dom}f}(y^Tx-f(x))\]is called the conjugate of the function $f$. The domain of the conjugate function consists of $y\in\mathbf{R}^n$ for which the supremum is finite, i.e., for which the difference $y^Tx-f(x)$ is bounded above on $\mathbf{dom}f$.

3.3.2 Basic properties

Fenchel’s inequality:

From the definition of conjugate function, we immediately obtain the inequality

\[f(x)+f^*(y)\geq x^Ty\]for all $x,y$. This is called Fenchel’s inequality (or Young’s inequality when $f$ is differentiable).

Conjugate of the conjugate:

The examples above, and the name ‘conjugate’, suggest that the conjugate of the conjugate of a convex function is the original function. This is the case provided a technical condition holds: if $f$ is convex, and $f$ is closed (i.e., $\mathbf{epi}f$ is a closed set), then $f^{**}=f$. For example, if $\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{R}^n$, then we have $f^{**}=f$, i.e., the conjugate of the conjugate of $f$ is $f$ again.

Differentiable functions:

The conjugate of a differentiable function $f$ is also called the Legendre transform of $f$.

To distinguish the general definition from the differentiable case, the term Fenchel conjugate is sometimes used instead of conjugate.

Suppose $f$ is convex and differentiable, with $\mathbf{dom}f=\mathbf{R}^n$. Any maximizer $x^*$ of $y^Tx-f(x)$ satisfies $y=\nabla f(x^*)$, and conversely, if $x^*$ satisfies $y=\nabla f(x^*)$, then $x^*$ maximizes $y^Tx-f(x)$. Therefore, if $y=\nabla f(x^*)$, we have

\[f^\*(y)=x^{\*T}\nabla f(x^\*)-f(x^\*)\]This allows us to determine $f^*(y)$ for any $y$ for which we can solve the gradient equation $y=\nabla f(z)$ for $z$.

We can express this another way. Let $z\in\mathbf{R}^n$ be arbitrary and define $y=\nabla f(z)$. Then we have

\[f^\*(y)=z^T\nabla f(z)-f(z)\]Scaling and composition with affine transformation:

For $a>0$ and $b\in\mathbf{R}$, the conjugate of $g(x)=af(x)+b$ is $g^*(y)=af^*(y/a)-b$. Suppose $A\in\mathbf{R}^{n\times n}$ is nonsingular and $b\in\mathbf{R}^n$. Then the conjugate of $g(x)=f(Ax+b)$ is

\[g^\*(y)=f^\*(A^{-T}y)-b^TA^{-T}y\]with $\mathbf{dom}g^*=A^T\mathbf{dom}f^*$.

Sums of independent functions:

if $f(u,v)=f_1(u)+f_2(v)$, where $f_1$ and $f_2$ are convex functions with conjugates $f_1^*$ and $f_2^*$, respectively, then

\[f^\*(w,z)=f_1^\*(w)+f_2^\*(z).\]In other words, the conjugate of the sum of independent convex functions is the sum of the conjugates. (‘Independent’ means they are functions of different variables.)

3.4 Quasiconvex functions

3.4.1 Definition and examples

A function $f=\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is called quasiconvex (or unimodal) if its domain and all its sublevel sets

\[S_\alpha=\\{x\in\mathbf{dom}f|f(x)\leq\alpha\\},\]for $\alpha\in\mathbf{R}$, are convex.

A function is quasiconcave if $−f$ is quasiconvex, i.e., every superlevel set $\{x f(x)\geq\alpha\}$ is convex. A function that is both quasiconvex and quasiconcave is called quasilinear. If a function $f$ is quasilinear, then its domain, and every level set $\{x f(x)=\alpha\}$ is convex.

Some examples on $\mathbf{R}$:

- Logarithm. $\log x$ on $\mathbf{R}_{++}$ is quasiconvex (and quasiconcave, hence quasilinear).

Ceiling function. $\text{ceil}(x)=\inf\{z\in\mathbf{Z} z\geq x\}$ is quasiconvex (and quasiconcave).

3.4.2 Basic properites

Quasiconvexity is a considerable generalization of convexity. Still, many of the properties of convex functions hold, or have analogs, for quasiconvex functions.

Like convexity, quasiconvexity is characterized by the behavior of a function $f$ on lines: $f$ is quasiconvex if and only if its restriction to any line intersecting its domain is quasiconvex. In particular, quasiconvexity of a function can be verified by restricting it to an arbitrary line, and then checking quasiconvexity of the resulting function on $\mathbf{R}$.

Quasiconvex functions on $\mathbf{R}$:

We can give a simple characterization of quasiconvex functions on $\mathbf{R}$. A continuous function $f:\mathbf{R}\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is quasiconvex if and only if at least one of the following conditions holds:

- $f$ is nondecreasing

- $f$ is nonincreasing

- there is a point $c\in\mathbf{dom}f$ such that for $t\leq c$ (and $t\in\mathbf{dom}f$), $f$ is nonincreasing, and for $t\geq c$ (and $t\in\mathbf{f}$), $f$ is nondecreasing.

3.4.3 Differentiable quasiconvex functions

First-order conditions:

Suppose $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is differentiable. Then $f$ is quasiconvex if and only if $\mathbf{dom}f$ is convex and for all $x,y\in\mathbf{dom}f$

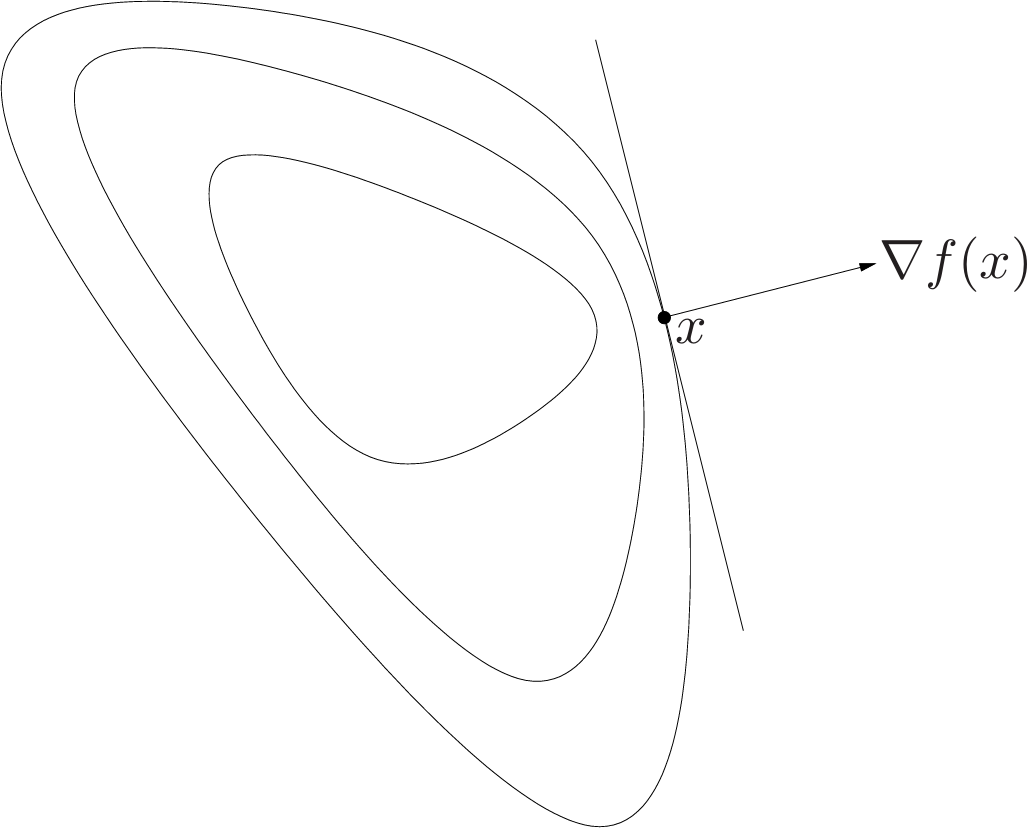

\[f(y)\geq f(x)\Rightarrow\nabla f(x)^T(y-x)\leq 0. \tag{3.7}\]| The condition (3.7) has a simple geometric interpretation when $\nabla f(x)\neq 0$. It states that $\nabla f(x)$ defines a supporting hyperplane to the sublevel set $\{y | f(y)\leq f(x)\}$, at the point $x$, as illustrated in fig. 8. |

| The vector $\nabla f(x)$ defines a supporting hyperplane to the sublevel set $\{z | f(z)\leq f(x)\}$ at $x$. |

While the first-order condition for convexity (3.2), and the first-order condition for quasiconvexity (3.7) are similar, there are some important differences. For example, if $f$ is convex and $\nabla f(x)=0$, then $x$ is a global minimizer of $f$. But this statement is false for quasiconvex functions: it is possible that $\nabla f(x)=0$, but $x$ is not a global minimizer of $f$.

Second-order conditions:

Now suppose $f$ is twice differentiable. If $f$ is quasiconvex, then for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$, and all $y\in\mathbf{R}^n$, we have

\[y^T\nabla f(x)=0\Rightarrow y^T\nabla^2f(x)y\geq 0. \tag{3.8}\]For a quasiconvex function on $\mathbf{R}$, this reduces to th simple condition

\[f^\prime(x)=0\Rightarrow f^{\prime\prime}(x)\geq 0,\]i.e., at any point with zero slope, the second derivative is nonnegative.

3.4.4 Operations that preserve quasiconvexity

Nonnegative weighted maximum:

A nonnegative weighted maximum of quasiconvex functions, i.e.,

\[f=\max\\{w_1f_1,\dots,w_mf_m\\},\]with $w_i\geq 0$ and $f_i$ quasiconvex, is quasiconvex. The property extends to the general pointwise supremum.

\[f(x)=\sup_{y\in C}(w(y)g(x,y))\]where $w(y)\geq 0$ and $g(x,y)$ is quasiconvex in $x$ for each $y$.

Composition:

If $g:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is quasiconvex and $h:\mathbf{R}\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is nondecreasing, then $f=h\circ g$ is quasiconvex.

The composition of a quasiconvex function with an affine or linear-fractional transformation yields a quasiconvex function. If $f$ is quasiconvex, then $g(x)=f(Ax+b)$ is quasiconvex, and $\tilde{g}(x)=f((Ax+b)/(c^Tx+d))$ is quasiconvex on the set

\[\\{x|c^Tx+d>0,(Ax+b)/(c^Tx+d)\in\mathbf{dom}f\\}.\]Minimization:

If $f(x,y)$ is quasiconvex jointly in $x$ and $y$ and $C$ is a convex set, then the function

\[g(x)=\inf_{y\in C}f(x,y)\]is quasiconvex.

| To show this, we need to show that $\{x | g(x)\leq\alpha\}$ is convex, where $\alpha\in\mathbf{R}$ is arbitrary. From the definition of $g$, $g(x)\leq\alpha$ if and only if for any $\varepsilon>0$ there exists a $y\in C$ with $f(x,y)\leq\alpha+\varepsilon$. Now let $x_1$ and $x_2$ be two points in the $\alpha$-sublevel set of $g$. Then for any $\varepsilon>0$, there exists $y_1,y_2\in C$ with |

and since $f$ is quasiconvex in $x$ and $y$, we also have

\[f(\theta x_1+(1-\theta)x_2,\theta y_1+(1-\theta)y_2)\leq\alpha+\varepsilon,\]| for $0\leq\theta\leq 1$. Hence $g(\theta x_1+(1-\theta)x_2)\leq\alpha$, which proves that $\{x | g(x)\leq\alpha\}$ is convex. |

3.4.5 Representation via family of convex functions

In the sequel, it will be convenient to represent the sublevel sets of a quasiconvex function $f$ (which are convex) via inequalities of convex functions. We seek a family of convex functions $\phi_t:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$, indexed by $t\in\mathbf{R}$, with

\[f(x)\leq t\Leftrightarrow\phi_t(x)\leq 0,\]i.e., the $t$-sublevel set of the quasiconvex function $f$ is the 0-sublevel set of the convex function $\phi_t$. Evidently $\phi_t$ must satisfy the property that for all $x\in\mathbf{R}^n,\phi_t(x)\leq0\Rightarrow\phi_s(x)\leq 0$ for $s\geq t$. This is satisfied if for each $x$, $\phi_t(x)$ is a nonincreasing function of $t$, i.e., $\phi_s(x)\leq\phi_t(x)$ whenever $s\geq t$.

Convex over concave function. Suppose $p$ is convex function, $q$ is a concave function, with $p(x)\geq 0$ and $q(x)>0$ on a convex set $C$. The the function $f$ defined by $f(x)=p(x)/q(x)$, on $C$, is quasiconvex.

Here we have

\[f(x)\leq t\Leftrightarrow p(x)-tq(x)\leq 0,\]so we can take $\phi_t(x)=p(x)-tq(x)$ for $t\geq 0$. For each $t$, $\phi_t$ is convex and for each $x$, $\phi_t$ is decreasing in $t$.

3.5 Log-concave and log-convex functions

3.5.1 Definition

A function $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is logarithmically concave or log-concave if $f(x)>0$ for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$ and $\log f$ is concave.

It is convenient to allow $f$ to take on the value zero, in which case we take $\log f(x)=-\infin$. In this case we say $f$ is log-concave if the extended-value function $\log f$ is concave.

We can express log-concavity directly, without logarithms: a function $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$, with convex domain and $f(x)>0$ for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$, is log-concave if and only if for all $x,y\in\mathbf{dom}f$ and $0\leq\theta\leq 1$, we have

\[f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\geq f(x)^\theta f(y)^{1-\theta}.\]In particular, the value of a log-concave function at the average of two points is at least the geometric mean of the values at the two points.

From the composition rules we know that $e^h$ is convex if $h$ is convex, so a log-convex function is convex. Similarly, a nonnegative concave function is log-concave. It is also clear that a log-convex function is quasiconvex and a log-concave function is quasiconcave, since the logarithm is monotone increasing.

3.5.2 Properties

Twice differentiable log-convex/concave functions:

Suppose $f$ is twice differentiable, with $\mathbf{dom}f$ convex, so

\[\nabla^2\log f(x)=\frac{1}{f(x)}\nabla^2f(x)-\frac{1}{f(x)^2}\nabla f(x)\nabla f(x)^T.\]We conclude that $f$ is log-convex if and only if for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$,

\[f(x)\nabla^2f(x)\succeq\nabla f(x)\nabla f(x)^T,\]and log-concave if and only if for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$,

\[f(x)\nabla^2f(x)\preceq\nabla f(x)\nabla f(x)^T.\]Multiplication, addition, and integration:

Log-convexity and log-concavity are closed under multiplication and positive scaling. For example, if $f$ and $g$ are log-concave, then so is the pointwise product $h(x) = f(x)g(x)$, since $\log h(x)=\log f(x)+\log g(x)$, and $\log f(x)$ and $\log g(x)$ are concave functions of $x$.

Simple examples show that the sum of log-concave functions is not, in general, log-concave. Log-convexity, however, is preserved under sums. Let $f$ and $g$ be log-convex functions, i.e., $F=\log f$ and $G=\log g$ are convex. From the composition rules for convex functions, it follows that

\[\log(\exp F+\exp G)=\log(f+g)\]is convex.Therefore the sum of two log-convex functions is log-convex.

More generally, if $f(x,y)$ is log-convex in $x$ for each $y\in C$ then

\[g(x)=\int_{C}f(x,y)dy\]is log-convex.

Integration of log-concave functions:

In some special cases log-concavity is preserved by integration. If $f:\mathbf{R}^n\times\mathbf{R}^m\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is log-concave, then

\[g(x)=\int f(x,y)dy\]is a log-concave function of $x$ (on $\mathbf{R}^n$).

It implies, for example, that marginal distributions of log-concave probability densities are log-concave. It also implies that log-concavity is closed under convolution, i.e., if $f$ and $g$ are log-concave on $\mathbf{R}^n$, then so is the convolution

\[(f\*g)(x)=\int f(x-y)g(y)dy.\]

3.6 Convexity with respect to generalized inequalities

3.6.1 Monotonicity with respect to a generalized inequality

Suppose $K\subseteq\mathbf{R}^n$ is a proper cone with associated generalized inequality $\preceq_K$. A function $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is called $K$-nondecreasing if

\[x\preceq_Ky\Rightarrow f(x)\leq f(y)\]and $K$-increasing if

\[x\preceq_Ky,x\neq y\Rightarrow f(x)< f(y)\]We define $K$-nonincreasing and $K$-decreasing functions in a similar way.

Gradient conditions for monotonicity:

A differentiable function $f$, with convex domain, is $K$-nondecreasing if and only if

\[\nabla f(x)\succeq_{K^\*}0 \tag{3.9}\]for all $x\in\mathbf{dom}f$.

Let us prove the first-order condition for monotonicity. Assume that $f$ satisfies (3.9) for all $x$, but is not $K$-nondecreasing, i.e., there exist $x, y$ with $x\preceq_{K}y$ and $f(y)<f(x)$. By differentiability of $f$ there exists a $t\in[0,1]$ with

\[\frac{d}{dt}f(x+t(y-x))=\nabla f(x+t(y-x))^T(y-x)<0.\]Since $y-x\in K$ this means

\[\nabla f(x+t(y-x))\notin K^*,\]which contradicts our assumption that (3.9) is satisfied everywhere.

3.6.2 Convexity with respect to a generalized inequality

Suppose $K\subseteq\mathbf{R}^m$ is a proper cone with associated generalized inequality $\preceq_K$. We say $f:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}^m$ is $K$-convex if for all $x,y$, and $0\leq\theta\leq 1$,

\[f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\preceq_K\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y).\]The function is strictly $K$-convex if

\[f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\prec_K\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y)\]for all $x\neq y$ and $0<\theta<1$. These definitions reduce to ordinary convexity and strict convexity when $m=1$ (and $K=\mathbf{R}_+$).

Dual characterization of $K$-convexity:

A function $f$ is $K$-convex if and only if for every $w\succeq_{K^*}$, the (real-valued) function $w^Tf$ is convex (in the ordinary sense); $f$ is strictly $K$-convex if and only if for every nonzero $w\succeq_{K^*}0$ the function $w^Tf$ is strictly convex.

Differentiable $K$-convex function:

A differentiable function $f$ is $K$-convex if and only if its domain is convex, and for all $x,y\in\mathbf{dom}f$,

\[f(y)\succeq_K f(x)+Df(x)(y-x).\](Here $Df(x)\in\mathbf{R}^{m\times n}$ is the derivative or Jacobian matrix of $f$ at $x$.)

The function $f$ is strictly $K$-convex if and only if for all $x, y\in\mathbf{dom}f$ with $x\neq y$,

\[f(y)\succ_K f(x)+Df(x)(y-x).\]Composition theorem:

Many of the results on composition can be generalized to $K$-convexity. For example, if $g:\mathbf{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbf{R}^p$ is $K$-convex, $h:\mathbf{R}^p\rightarrow\mathbf{R}$ is convex, and $\tilde{h}$ (the extended-value extension of $h$) is $K$-nondecreasing, then $h\circ g$ is convex. This generalizes the fact that a nondecreasing convex function of a convex function is convex. The condition that $\tilde{h}$ be $K$-nondecreasing implies that $\mathbf{dom}h−K=\mathbf{dom}h$.